NASA completes balloon campaign in Antarctica • Space Perspective unveils hardware for future manned flights • Two new manned balloon flights by Iwaya Giken in Japan • Aerostar activity and some questions • In brief

Well, what was intended to be the last edition of 2023 has become the first one of 2024. It’s been a rough time lately for me so just recently I had enough spare time and will to write up the latest developments in the lighter-than-air field. A couple of things were left out from #24 to prevent everything from being delayed further. These will probably see the light in the next edition soon.

Enough for an introduction. A late happy New Year for everyone, and let’s go into business…

NASA completes balloon campaign in Antarctica

NASA's balloon program has had some problems lately with several missions whose balloons experienced in-flight failures (EUSO-SPB and Fireball in 2023). In that sense, the Antarctic campaign that has just ended is a good example of this and although we know that the white continent is one of the most hostile environments to develop an activity as climate-dependent as scientific ballooning, the reality is that the agency is experiencing the same type of problems on its flights regardless of the weather or location.

Although all the headlines are being monopolized by the excellent performance that the flight of the GUSTO telescope is having so far, the reality is that the other two missions carried out by the agency - little or nothing mentioned in the media- did not end well.

Let's go in chronological order.

The first balloon launch of the campaign occurred on December 11th. Balloon mission 735NT was devoted to a technological test by the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility of solar panels for future use in long-duration flights and used a small zero-pressure balloon that was hand-launched (note: really it is launched using a roll-based device known as the “Hutch clutch” system and not by hand).

The balloon performed a nominal ascent and reached as expected a float altitude of 125.000 feet a few hours later. However, in the following days, it started to lose altitude steadily. That’s in part the reason that in the map above, the flight path of the aerostat acquired that odd pattern instead of the circular counterclockwise route around the pole. By Christmas Eve it was below 100.000 feet.

Finally, the mission was terminated on December 26 at 18:30 UTC. Landing occurred in the Ronne Ice Shelf, 170 km S of the Argentinian Belgrano II base after a total flight time of 15 days and 17 hours.

No official word was issued by NASA on the apparent failure.

The second balloon was launched as mission 736N after several attempts in previous days and following periods of really bad weather. Onboard was GUSTO acronym for Galactic/Extragalactic ULDB Spectroscopic Terahertz Observatory. The instrument is a telescope equipped with very sensitive detectors that will measure emission lines for carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen to obtain a deep insight into the full lifecycle of the interstellar medium, the cosmic material found between stars.

Originally, the balloon used on this mission would be a super-pressure one, but during pre-launch operations was evident that something had changed as the extraction of the balloon from its box and inflation proceeded as usual for a zero-pressure balloon.

Days later I found some quotes about the reason for the change was because the Super-Pressure balloon is still in the process of qualification and not fully reliable yet. Sadly I lost the link to the reference so you're going to have to trust my word (you better…)

The picture-perfect launch occurred at 6:35 UTC on December 31st so GUSTO became the very last balloon launched of the year 2023. The balloon ascended very slowly and finally reached a mean float altitude of 125.000 ft that so far maintained during January. In early February, the balloon started to lose altitude during some periods. The altitude variation is pretty constant reaching as low as 110.000 feet and after a few hours, the balloon recovers the initial height of 125.000 ft. In my humble opinion that behavior could be due to the cooling of the gas inside the balloon at the moments when the Sun is lower in the sky.

At the moment of writing this, the balloon has been aloft for more than 48 days and is transiting its third turn to the pole, which probably will not be fully completed as in the last days its circular trajectory is deteriorating and acquired an odd pattern, typical of a polar vortex that is dissipating.

Although the goal is to fly at least for 55 days is good to remember that GUSTO is a “throwaway” mission. ¿What does it mean? unlike occurs with all the payloads launched by NASA in the white continent, GUSTO has been planned for not to be recovered at the end of the flight. As probably the polar vortex will break up by the time the telescope's mission approaches to the end (ie: the onboard cooling gas for detectors depleted), the payload will be taken by the prevailing winds outside the continent and will be finally sunk in the ocean.

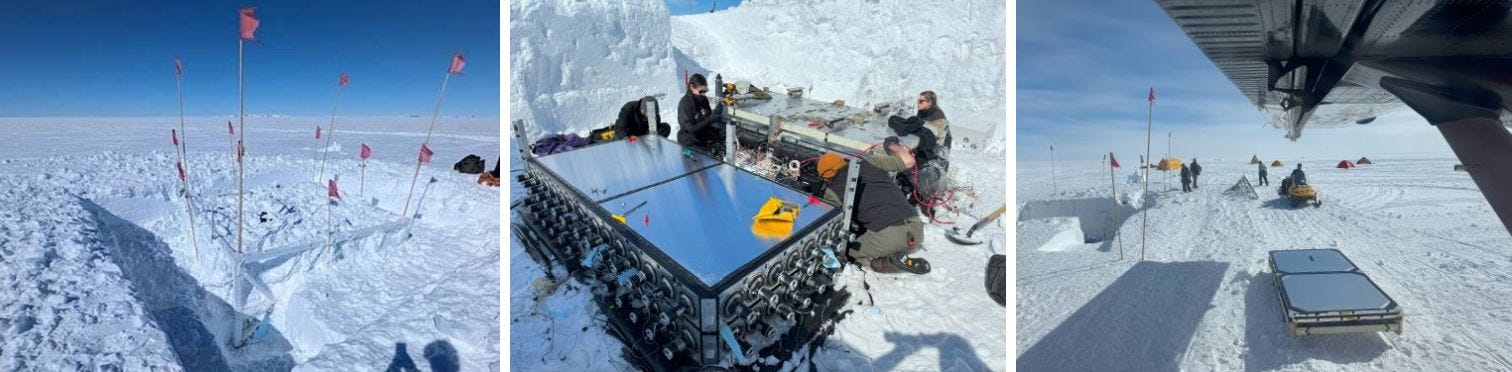

Talking about recoveries, please let me deviate for a moment from the chronological account of the campaign to mention a peculiar event that occurred almost parallel to it. But we need first to make some history. In December 2019 a balloon-borne instrument called Super-Tiger II was launched in Antarctica and made a very successful trip around the pole in 32 days. The payload landed about 489 miles from McMurdo Station. A few days later a first rescue expedition arrived at the landing site and recovered high-priority items hoping for a full recovery next season. However, due to logistical constraints and cancellations of the next two launch campaigns the payload would remain on the ice for FOUR YEARS.

During the current season, a team from Washington University at St. Louis dubbed the “SuperTIGER Rescue Rangers” arrived at McMurdo with the mission of recovering the rest of the payload. As it landed upside down, the work to reach the detectors of the instrument required an intense job of digging the snow to unearth it from the ice, which was performed to a big extent by staff of the US Antarctic Service.

The team made several trips to the landing site and after a few days of work on the ice, the disassembled payload was loaded in a Bassler transport plane, returned to McMurdo, and shipped back to the States.

After this brief detour in the chronological story, lets return to the campaign itself.

The third and last mission of the NASA Antarctic campaign would become the first one launched in 2024, but unfortunately, it also would suffer a balloon failure.

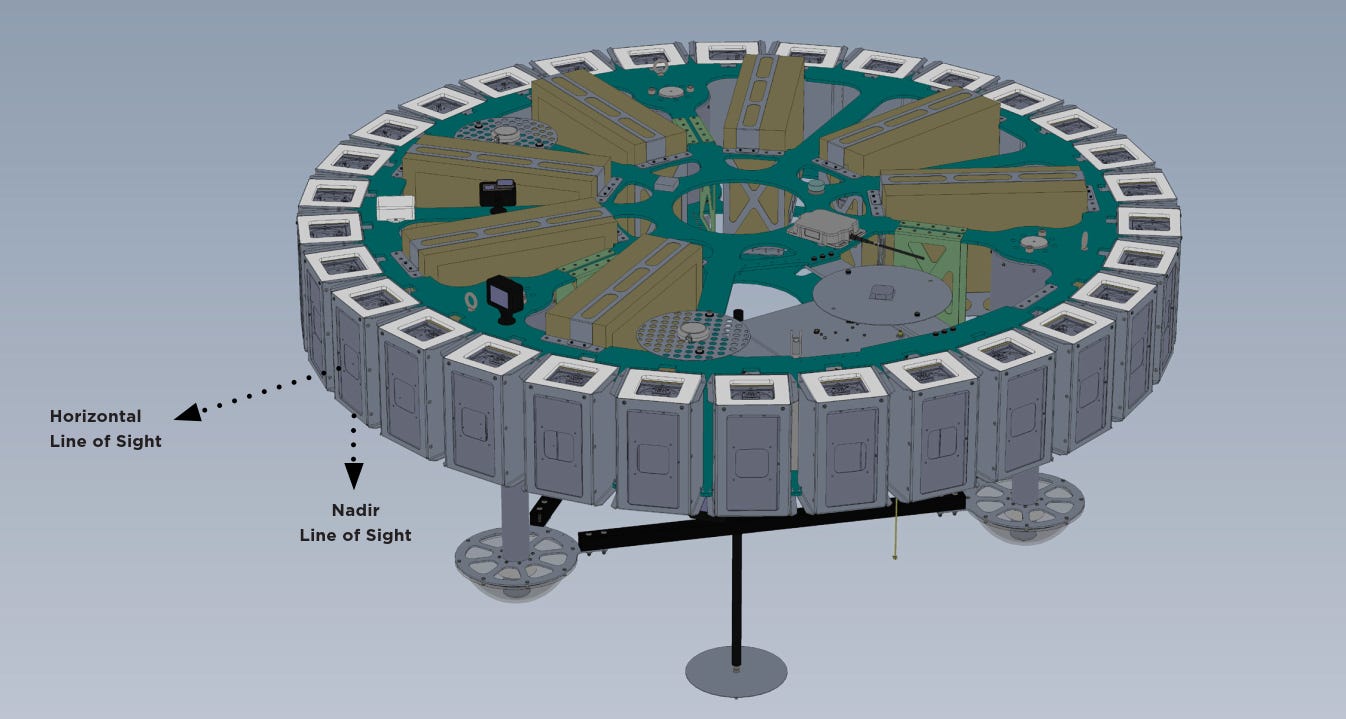

The mission numbered as 737NT transported an instrument called AESOP-Lite, (an acronym for Anti-Electron Sub-Orbital Payload) developed by the University of Delaware and the University of California, Santa Cruz to measure cosmic-ray electrons and positrons. A secondary payload onboard was ANIHALA (Antarctic Infrasound Hand Launch) whose objective was to measure natural background sound in the stratosphere over a continent where human-generated sound is largely absent. This is a cooperative mission between the Swedish Institute of Space Physics and Sandia National Lab. from the United States.

A remarkable aspect of the mission was that it was launched using a 60 million cubic feet zero-pressure balloon, the largest in NASA's inventory and also the largest ever launched in the white continent. The balloon -manufactured by Aerostar International- would allow AESOP-Lite to reach extremely high altitudes surpassing 150.000 feet for weeks.

After numerous canceled attempts in previous days (in fact, according to some sources the launch took place an hour before the closing of the launch window on the last possible launch day for the season), the balloon finally got in the air on January 10, 2024 at 2:33 utc.

The balloon started a slow ascent and reached soon a maximum altitude of 156.000 ft which I dare to affirm is the highest ever reached by any balloon flown on the white continent. However, the good news won’t last.

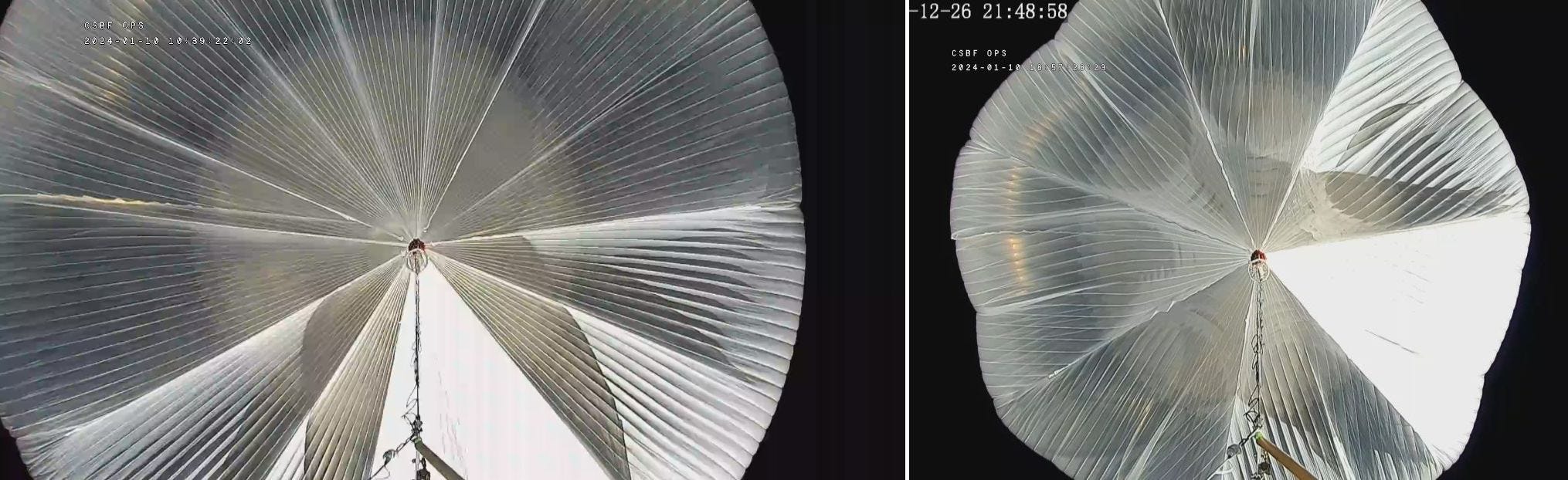

A few hours after reaching maximum height the balloon started to experience a slight but constant loss of altitude. By 19:00 utc the balloon lowered to 144.000 ft and its shrinking was quite evident in the images transmitted by CSBF.

As hours passed, the altitude loss remained constant, evidencing what we all feared: the presence of some type of leak in the balloon well beyond any probable recovery, even dumping all ballast available.

Finally, on January 12 the mission was terminated at about 7:30 UTC. The payload landed in the Antarctic Plateau, 77 km NE of the natural formation called Dome Argus. By the time the flight ended, the BIG60 had reached its minimum altitude of 113,000 ft. The total flight time was 46 hours.

Since the end of the campaign, NASA remained silent regarding both failures and made no mention of the early termination of the BIG60 / Aesop-Lite mission on its scientific ballooning website.

We will likely have to wait a few months until the pertinent explanations are made public, either by the agency or by the operators of the scientific payloads.

The contents of this newsletter as well as the entire StratoCat website are free and available to all readers and will continue to be that way. I didn't even want to subject eventual visitors to the torture of advertisements. However, if you want, you can help to keep this project alive with just the amount of a cup of coffee.

Space Perspective unveils hardware for future manned flights

As you know, I’m trying to maintain this humble newsletter outside the hype of the incipient and overpopulated balloon-based tourism industry. Many of you know what I think about it. However, when in my opinion there are real advances toward the objective of near-space manned missions, and not merely marketing operations (no talk about cookies prizes, luxury cars, exuberant meals and the like) I will be more than happy to include them here. And this is precisely the case with Space Perspective, the Florida-based company, that back in December presented in real life the prototype of the capsule to be used in the manned tourist flights the company is planning to offer starting in 2025.

The circular pressurized carbon-composite sphere, which was manufactured at a Melbourne factory, is now being readied at a hangar the company had in their Titusville Regional Aiport facility. The current work includes the installation of 15 windows (manufactured in California) and the addition of systems to handle temperature control, life support, communications, navigation, and other equipment.

By January, the company announced the completion of the structure of that first capsule, which has been named “Excelsior” as a tribute to the famous project of the same name, conducted by the USAF in the late 1950s and whose main protagonist was the late Col. Joseph Kittinger.

The capsule will take part in more than ten uncrewed tests, and some manned flights too. Meanwhile, a second capsule to be used in commercial missions will be constructed and tested with humans onboard, ahead of the first paid passenger trips.

Along with the capsule, Space Perspective announced the completion of the overhaul process of the ship acquired by the firm in 2022 which served in the oil industry and now will be used as a departure and landing point for the balloons.

The vessel, an Offshore Support Vessel or OSV built by Edison Chouest Offshore was originally named Challenger and now has been rebaptized Marine Spaceport Voyager honoring the Voyager 1 space probe, which shot the infamous Pale Blue Dot image on Carl Sagan's request in 1990, and Voyager 2, which became the first and only spacecraft to visit Neptune.

A lot of adaptations were necessary to adequate the vessel for its new task, but the main modification was in her length. Originally the ship was 83 m long, but considering that it would operate with huge balloons the rear was extended almost seven meters, bringing it to 90 m (294 ft) overall. It is powered by more than 8,000 horsepower and holds onboard generators that produce over 1 megawatt of electricity. Voyager’s precise mobility and dynamic positioning are made possible by two bow thrusters (one of which rotates a full 360 degrees) and two stern thrusters that rotate 360 degrees.

The uncrewed test flights of the Excelsior capsule would commence now on Q1 in 2024 to obtain the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certificates. If all goes according to plan, Space Perspective will be the fourth company to receive a licensed commercial vehicle for human flight, joining SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic.

Two new manned balloon flights by Iwaya Giken in Japan

The Hokkaido-based firm Iwaya Giken continued its step-by-step approach and tested in flight during the last part of 2023 and early 2024 the two-seat model of their balloon-borne capsule, that will be used in the future to transport passengers to the stratosphere. Both tests were conducted in the town of Makubetsu, located in Tokachi Subprefecture, Hokkaido.

Operation of the T-10 capsule EARTHER (which is very reminiscent of a somewhat flattened version of the cockpit of a WWII B-29 plane) started in November with a tethered ascent to ensure safety measures, rehearsal of operational procedures, and to test the stability of the vehicle under the balloon.

The first free flight of the T-10 was carried out on December 6, 2023. The capsule with two pilots on board ascended to 700 meters and remained in flight for 90 minutes. During the mission were practiced several manouvers including the operation of the valve of the balloon and leveled flight by dropping ballast. The mission was completed with a successful landing on the riverbed of the Tokachi River. There is a short video of several moments of the flight on Iwaya’s YouTube channel.

The second test was conducted by the same crew on January 4th, 2024. The goal of the flight this time was to improve the accuracy of the control of the vehicle. A video of the flight is also available.

Aerostar activity and some questions

During the more than two months that passed since the last issue of this bulletin, there was not much activity on the part of Aerostar the South Dakota-based balloon firm. However, as the saying goes sometimes less is more.

Regarding the new launches, during the period we had five missions performed of which one is still in the air at the moment of writing this.

Let’s go chronologically as usual.

The first launch nomenclated as HBAL 670 took place on December 7th, from the undisclosed site that Aerostar has in Santa Fe County, not far from Moriarty. The Thunderhead balloon was launched at about 13:10 UTC and remained in flight for a little more than 2 days before landing near Plainview, Texas.

The company closed in the year 2023 with an isolated flight performed from Fox Run Regional Park near Colorado Springs. The mission with call sign HBAL 671 remained in flight for a little more than 6 hours landing in Kansas, near Sharon Springs. So far, this is the first launch by Aerostar from there.

Already into the year 2024, the first launch of the company took place as HBAL 672 from Hurley (SD) on January 20. The mission ended in Iowa after 7 hours of flight.

The launch routine was somewhat altered the very next day, when we had the sudden return to most plane tracking apps of HBAL 661 a Thunderhead balloon that was launched on October 23rd from Hurley and went off the grid over the Pacific Ocean by mid-November. The balloon popped up above the Cortez Sea off Baja California and crossed Mexico and the United States moving towards the northeast. It finally landed near Woodstock, Minnesota on January 26 completing a remarkable hemispheric tour of 95 days.

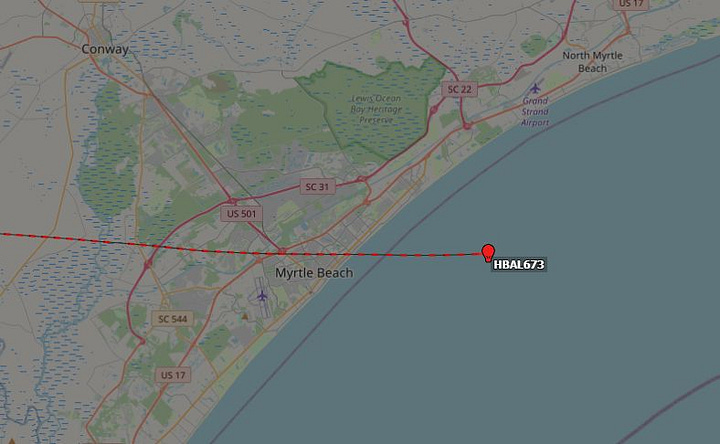

On January 25, the activity focus shifted back to New Mexico with the launch of a Thunderhead balloon with call sign HBAL 674 but apparently, it suffered some kind of problem in flight and was terminated merely three hours after launch. It would be followed two days later by HBAL 673 which succeded in crossing the United States eastbound almost unnoticed. However, approaching the east coast and just before being off the grid over the Atlantic Ocean the balloon gained some headlines in the news and social media as it appeared over Myrtle Beach, in South Carolina near the first anniversary of the infamous incident with the Chinese Spy Balloon.

At the time of wrapping up this edition, the balloon was in flight off the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua in Central America.

In the past issue of World Balloon News I mentioned a balloon flight the firm performed from its flight facility in Hurley (SD) on November 29. Recently, Aerostar published more details of the flight on its website, which is quite remarkable as it was the first Thunderhead super-pressure balloon system using hydrogen as lift gas.

I know. Hydrogen.

There are several reasons to do so, but the main one is its availability, and as a consequence, a sharp reduction of operative costs of ballooning. The big issue with hydrogen is on the safety side. Without having to resort to well-known images of the Hindenburg disaster, there are many examples in the scientific ballooning history of hydrogen igniting balloons during inflation or after release. A little static discharge or carelessness is all it takes to cause an explosion.

I will not reproduce here the details of the test which you can read for yourselves on the company's website. Instead, I will share a couple of thoughts on this (which obviously can be debatable).

The company is not the first to show an interest in the use of hydrogen. Many balloon programs around the world simply can’t afford the price of helium and developed over the years their activity solely based on the flammable gas. India, Brazil, and Argentina are some examples of that.

In the case of Aerostar, in my opinion, this gas replacement strategy may apply only to short-duration test flights. I doubt that would be advisable to use hydrogen in missions that may not only venture outside the US but even into remote areas of the United States.

What would happen if one of the balloons on its descent hits a high-tension line?

Also, taking into account that these types of balloons descend along with their payload, what could happen if someone finds one with some hydrogen still inside before the recovery teams arrive?

What if that happens in some remote area of another country or an extremely dry area at risk of fire?

I think they are uncomfortable but more than necessary questions to ask ourselves, what do you think?

In Brief

The year 2023 ended with some interesting news regarding the infamous affair of the Chinese Spy Balloon that crossed the US airspace before being downed by an F-22 Raptor off the coast of South Carolina nearly a year ago. One week apart on December 22nd and 29th, NBC News published two reports on the matter, the first entitled "The secret U.S. effort to track, hide and surveil the Chinese spy balloon" on which officials from the Biden administration said that the threat posed by the balloon was exaggerated, while military officials contended that too little has been done to detect high-altitude spy balloons. The second one entitled "U.S. intelligence officials determined the Chinese spy balloon used a U.S. internet provider to communicate" developed over some revelations from intelligence sources on the fact that the balloon sent and received communications from China, primarily related to its navigation, but also found that the connection allowed the balloon to send burst transmissions, or high-bandwidth collections of data over short periods.

NASA selected the 30 projects to fly on a World View balloon this summer as part of the 3rd. TechRise Student Challenge. Each team will receive $1,500 to build their experiments, a flight box to house them, technical support, and an assigned spot for their experiments on the multi-payload gondola which will be launched under a Stratollite long-duration balloon from the Page Municipal Airport in Arizona. The list of winners and their experimental goals is available on the Future Engineers website.

A new podcast is available for Spotify and Apple users entitled “The Race to Near Space”. The piece is run by the HAPS Alliance, a conglomerate of companies from telecommunications, technology, aviation, and aerospace industries that promote the use of high-altitude platform stations in the stratosphere. The podcast launched in September 2023 counts so far with two episodes: an interview with Alan Eustace (pilot of the STRATEX initiative) and a conversation with Aerostar’s Russ Van Der Werff

On January 13th, an online conference was held by Space Place Canada, entitled Astronomy from the Stratosphere: Balloon-borne Telescopes, with a very interesting presentation by Emaad Paracha, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Toronto and a member of the scientific team behind SuperBit, the balloon-borne telescope launched in 2023 from Wanaka, New Zealand that flew 40 days under a NASA super-pressure balloon in the southern hemisphere before crash-landing in Argentina. For all of you who missed the event, the conference is available on YouTube.

As occurs every end of the year, Aerospace America, the magazine of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), published on its website a summary of the most relevant advances in the field during 2023. Under the title "Preparing for passenger balloon flights to the stratosphere and scientific flights to Venus" Sarah Roth and Paul Voss break down what in their opinion were the most relevant events for the sector.

That’s all folks for this… week, month, whatever. See you soon, and remember, if you like the contents of this humble newsletter, please share it with those who could be interested and help me to widen the audience.